Chapter the 327th, where RTD's turning Doctor Who into a soap again!

Plot:

[A recent story of the streaming era, so be warned there are spoilers ahead.] The Doctor, trying to get Belinda back to the 24th May 2025, materialises the TARDIS in 1952 Miami to take a triangulation reading with a gizmo. The local cinema is closed and locked: three months ago, 15 people went missing there. The projectionist Reginald Pye seems to be showing films to an empty auditorium. The Doctor can't resist investigating, to find that the films are being played to Mr. Ring-a-Ding, a cartoon character come to life, who is feeding off the light; widower Pye has been tempted to do this because the cartoon - really another member of the Pantheon of Discord, god of light Lux - brought Pye's dead wife back to life from an old home movie. Lux has done the opposite to the missing people, trapping each in a frame of celluloid. He also does this to the Doctor and Belinda, rendering them two-dimensional inside a cartoon film. The TARDIS team work out that they can use emotional feeling to give themselves depth and dimensionality; this returns them to normal, but they are still trapped. Attempts to scroll the film up or down, or to break through it outward, just lead the pair into illusory scenes Lux has created to toy with them; at one point, the Doctor meets fans of his TV show, but it's not real (or is it?). Eventually, the Doctor realises they have to hold the film frame still, let the projector burn through it, then they can escape. Back in the real world, the Doctor heals his burnt hand with spare bi-regeneration energy. Seeing this, Lux captures the Doctor and feeds off the energy, growing and starting to become three-dimensional. Pye sacrifices himself, aiming to be reunited with his wife, by blowing up the projection room. Sunlight comes in from outside - this energy is too much for Lux who grows and grows until he becomes one with the light of the universe. The Doctor is freed and the missing people reappear.

Context:

A new series of Doctor Who has begun, and is underway as I write this. It's the seventh to kick off since I began the blog; it might turn out to be the last, if you believe what you read in the papers (see Deeper Thoughts below for more on that). The blog has needed the injection of vitality that a new set of episodes brings (last time I was reduced to blogging an episode of Class, for Amdo's sake!); as soon as the season started, I fired up the random number generator to select the first story of this new run to blog, and it chose Lux. A few days after I saw it for the first time, I watched it again taking notes (the middle child, boy of 15, who'd watched it with me first time - see below - came in, sat down and watched it all again, he enjoyed it that much first time round).

Milestone watch: I've been blogging new and classic Doctor Who stories in random order since 2015, and I'm now closing in on the point where I finish everything and catch up with the current stories being broadcast serially. This post marks the first story covered from the 41st season (or 15th or 2nd depending on your numbering protocol), Ncuti Gatwa's second run. It looks like the last two episodes of the run will form a 2-part finale, so there are six stories remaining after Lux to blog in random order. Beyond that, I've completed ten Doctors' televisual eras (the first, third, fourth, seventh, eighth, ninth, eleventh, twelfth, thirteenth and fourteenth Doctors) and 36 out of the 41 seasons to date (at the time of writing): classic seasons 1-5, 7-18, 20, 21, 23-26, and new series 1, 2, and 4-14.

First Time Round:

Even though a lot of people moaned about it in 2024, I liked the midnight iplayer launch time for new episodes of Gatwa's first series, and made a point of staying up to enjoy each week's new offering. I hadn't, though, formed any habit by the time Lux dropped of watching at the new time of 8am on Saturday morning (many - just as many? - people moaned about this new time, of course); instead, I got round to watching it at about 6pm on the 19th April 2025, an hour before it was going to be shown live on BBC1, from the aforementioned iplayer streaming service. As such, if I understand the methodology correctly, had our house's TV been one of those 5000-ish in the UK with BARB 'peoplemeters' attached to capture ratings, our viewing would not have been included in the overnights. This, despite at least two big Doctor Who fans (me and the middle child) living in the house. This just goes to show how pointless a measure they are (see Deeper Thoughts below for more on that). Both of us audibly gasped and looked at each other with wild excitement in our eyes at the reveal of Mr Ring-a-Ding's laugh, and both agreed afterwards that the story had been an effective and enjoyable one. The next day, the eldest (young man of 18) made a point of messaging me - he's away at university currently - to tell me how he too had much enjoyed the story.

Shortly after Lux's broadcast, I was amused to see a fan review on a website whose headline read 'It's messy and weird, but "Lux" feels more like Doctor Who again'. What amused me particularly was the word 'but', and to a lesser extent the words 'more' and 'again'. It's messy and weird, "Lux" feels like Doctor Who - that's more like it. What had the writer been watching previously that they'd got the idea that Doctor Who feels like Doctor Who despite the weirdness and messiness? Messy and weird were built in to the show from the very beginning, and Lux was an effective continuation of that tradition. Don't get me wrong, though, the messiness I'm talking about is the show's slippery nature regarding classification: people looking for hard science fiction, for example, might have been disappointed by the more fantastical Lux, but the Next Time trailer at the end for following story The Well, with lots of soldiers in futuristic gear with blasters, would hopefully have piqued their interest. Doctor Who is messy because it can morph into dozens of different things, often within the space of one story. This indeed happened in Lux, the 'meta' sections in the middle allowing the story to playfully comment on itself. What was not messy was the production design and effects work, which was superb and precise throughout. Lux is visually stunning, the evocation of early 1950s Miami in 2020s Wales was such that the viewer was fully immersed from the off. The interaction of animation and live-action throughout was seamless. The extra budget has been wisely spent creating new and engaging concepts for use in the show: a cartoon come to life, live-action characters turned into animation, live-action black and white characters interacting with others in colour. That this 60+ year old show is still finding new things to do makes every cent from the Disney+ co-production deal worthwhile.

The script mines every moment it can from the imaginative jumping off point of characters being able to jump off, and back on to, film frames. Once the Doctor and Belinda are turned into two-dimensional cartoons, the narrative runs through each of the obvious actions that they might take to escape, visualising each perfectly within the cartoonish reality that's been established. They use their emotions to make themselves become more and more three-dimensional (a neat way to allow the Doctor and his new companion to share detail about themself to the other without it being an info-dump), they move the film up and down, they hold it still so it starts to burn with an evocative projected celluloid melting and bubbling effect. This is catnip to the young and not so young viewers who want their imagination to be engaged. In the most bravura sequence, the TARDIS team go outwards rather than up or down, literally breaking the fourth wall. The Doctor and Belinda then get to meet three Doctor Who fans within the story world of the programme itself. It's a very funny sequence: the three fans are positive, but not uncritical; through them, writer of the story and show-running executive producer Russell T Davies gently chides himself - and/or the conventions of genre screenwriting - for the overt seeding in of the mechanism that will be crucial in the denouement (with fan Robyn harking back to a line of dialogue about old film being highly flammable), and for never being able to write something as good as Blink (all three fans' favourite story, much better in their eyes than the ones with the goblins, the Beatles or the Doctor standing on a land mine). Just when one might think that the story's disappearing up its own metaverse, it turns poignant: the three Doctor Who fans know they're not real, and they know that it doesn't matter.

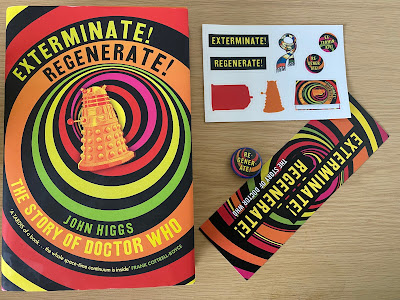

Even though they are just part of an illusion created by Lux to toy with the Doctor, Lizzie, Hassan and Robyn's appreciation for the Time Lord has taught them to be cleverer than Lux; they can help the Doctor escape, even if it means they'll blink out of existence. In the scene, Davies also celebrates the power of Doctor Who to bring people together, this being the way that the three fictional best friends met. Towards the end of the scene (my eyes were not dry by this point, I'm not ashamed to admit), Lizzie says "Maybe, just now and then, you can think of us - then we might live on just a little bit". In a mid-credits scene all three are revealed to have continued on, so presumably the Doctor did just that. The Doctor lives beyond the confines of a screen because he's lodged in the minds of his fans, and now he gets to return the favour and the reverse is true too. Having just finished John Higgs's Doctor Who book (see the Deeper Thoughts of this blog post for more details), I'm guessing he'll have loved all this, it being in line with his theory about the character of the Doctor having outgrown the bounds of fiction. The script also has time to touch on the fear and potential of the early atomic age, AIDS, and the injustice of segregation. The Doctor, in dialogue that's sure to be on a T-shirt one day says "I have toppled worlds; sometimes, I wait for people to topple their world - until then, I live in it and I shine!". There's lots of great dialogue ("I'm a two-dimensional character, you can't expect backstory"), some scary moments (the three-dimensional Mr. Ring-a-Ding is wonderfully creepy), and a great ending: the light of the sun is so powerful that Lux goes from fake to true godliness ("Invisible... intangible" / "Amen!").

Any criticisms I could make would be the tiniest motes of dust, nothing as big as a hair in the gate. Linus Roche is lovely in an understated way as Reginald Pye, but the character's death scene isn't perfectly staged. He's doing the noble sacrifice, so should just stay still in the room with the film on fire not leave it and close the door (which makes it look like he's trying to escape and confuses the issue momentarily of whether he survived or not). The story is essentially just a slightly more successful repeat run of The Devil's Chord, with the reels of film wrapping the Doctor up exactly as the musical scales did to Ruby Sunday, plus many other parallels. Alan Cumming's great vocal work as Mr. Ring-a-Ding / Lux can't quite get up to the camp levels of Jinkx Monsoon's full, live-action appearance as Maestro, but he gives it a hell of a good go. The parallels are almost certainly deliberate, this being another run-in with the Pantheon in the exact same place in the running order of the season. Any repetition is worth it for those of us (like me and the middle child) who are invested in the ongoing plotline. There will likely be more run-ins with members of the Pantheon before the end of the season. Is Mrs. Flood one of them? She time-travelled for the first time in Lux, appearing in Miami at the end to tell all that the Doctor's time is nearly up: his limited run ends on the 24th May 2025. In real life it doesn't, of course. That's the date of the penultimate episode of the run, hinting that the episode shown on 31st May 2025 will have to be even more apocalyptic to top it. I'm excited to see how it all pans out.

Connectivity:

This is a neat one: the forces of antagonism in Lux and the Class opener For Tonight We Might Die are, respectively, anthropomorphised light and anthropomorphised shadow.

Deeper Thoughts:

The Metrics Reloaded. Without meaning to discount all the craft and talent that goes into it, Doctor Who is a product of industry (as all TV programmes are). As such, there will be measures by which it is judged by the industry involved in its making. The most obvious of these, but not necessarily the most useful, are ratings. As recently commented upon here (in the Deeper Thoughts section of the recent blog post for Slipback), the UK tabloid press had been happily spreading rumours about the bleakness of Doctor Who's future for months before Ncuti's second run started. No fan - and probably no journalist - knows anything to help them predict the future. Any fan or journalist, though, could have predicted what would happen once the first overnight rating for Gatwa's second run was recorded. After weeks of articles speculating based on no data, there would be another spate of articles making the same speculation but this time based on just one datum. There was no realistic figure for the overnight rating of The Robot Revolution that would have silenced the speculation; it would have had to be something like 8 million, I think, for the online warriors of the UK tabloids like the Express, Mail or Mirror to have shelved the copy that they'd probably already written about how 'Doctor Who's woes continue', or whatever. As it was, it got 2 million, not far from what it was getting for overnights last year, but slightly down. It was the fourth largest overnight of the day, second for the BBC behind Gladiators with 2.9 million - one tabloid categorised the pumped-up shiny game show as having a "whopping" lead over our favourite Time Lord's latest adventure. The suggestion that 2.0 million is disappointingly small but 900,000 is impressively large seemed illogical to me.

It's not mandated for tabloid journalism to be logical, of course. If it were, then those writing it might consider that the figures for people watching a show in a particular broadcast slot on a TV channel aren't as relevant when that show is a streaming-first prospect. Arguably, they aren't relevant for any show: I now consume zero BBC programmes except through the iplayer, and I doubt I'm alone in that. Anyway, logic dictates a decision about Doctor Who's future is based on the metrics important to Disney+ rather than anything to do with UK broadcast. It's not mandated for international streamers to be logical either, of course. The metrics are often opaque, but there's been many a time when by any visible indication (such as a vocal fanbase clamouring for a recommission) shows that are popular still get canned by the streamer, often after just one or two series. There might be nothing that can be done, and we could be about to see Doctor Who come to an end (at least temporarily). Given that we fans are powerless, we may as well stop worrying. Instead, we could have a look at metrics about our favourite show that are more fun. For example, at three letters long, Lux has the second shortest title of any story in Doctor Who's history. Given that all the other titles for this year have already been published and they're longer, and given that the shortest title ever (2007's David Tennant-starring '42') comprises just figures, Lux could be accurately said to win the prize for the fewest number of letters used for a Doctor Who story title. If the show does come to an end, it will keep that prize for some time, perhaps for ever. There are obviously periods in Doctor Who's history where it's difficult to compare ratings, as the broadcasting landscapes of those times were disparate. Somehow, our funny, lovable, weird and messy show manages to make the same true even for a metric as simple as the length of story titles...

Early on, stories didn't have overall titles on screen; the same is true in more recent years. The early period has unofficial titles; for the recent period, people tend to use all the linked episode titles chained together. Even both those approaches have points of contention, though. Accepting that some might disagree, I can tell you that in its first eleven years, production teams eschewed very short story titles; shortest were The Ark (six characters and a space) in 1966 and Inferno (7 characters) in 1970. It's not until Tom Baker takes over that there's a story title of five characters (his debut, Robot). There was one more of that length (Kinda) plus another that never made it to screen (Shada), but no classic era story title with fewer characters. When the show returned in 2005 it breached that lower limit; the very first story title was four characters long (Rose) and that became a relatively common length later (Hide, Rosa, Flux, Boom). As for the longest story title, the classic series champion is Doctor Who and the Silurians (28 characters including spaces) but the inclusion of the first three words of the title on screen was a clerical error. The new series winner could be Utopia / The Sound of Drums / Last of the Time Lords (52 characters including spaces and separators) but there's disagreement about whether that first episode is part of the overall story or standalone. Without Utopia, it loses out to Ascension of the Cybermen / The Timeless Children (49 characters including spaces and separators). If multiple titles linked by separators feels too much like cheating, then the winner is Matt Smith Christmas special The Doctor, The Widow and the Wardrobe (38 characters including spaces and punctuation). That feels like it could potentially be bested one day. But, even if the programme's future proves less bleak than speculated, it seems unlikely that there will be many more story titles of three or two characters' length.

In Summary:

Lux-uriously good.